Escaping the feature factory: lessons from Touchpoint and Phishbite

I’ve seen both sides of product building: chasing features that never launch, and focusing deeply on solving one painful problem. I share in this article both of these.

Most startups don’t die from a lack of features. They die from building too many.

I’ve been building Phishbite with my co-founders Henrik and Mikk for two years. Along the way, I’ve faced the same trap most product leaders and founders know too well: the feature factory mindset.

I’ve spent hours with Henrik debating how we should measure success, not by how many features we release, but by the problems we solve and the value we create.

This mindset didn’t come naturally. It was shaped by my earlier experience at Touchpoint, where I learned the hard way what happens when you chase features instead of value.

Why features feel so seductive

On the surface, features look like progress.

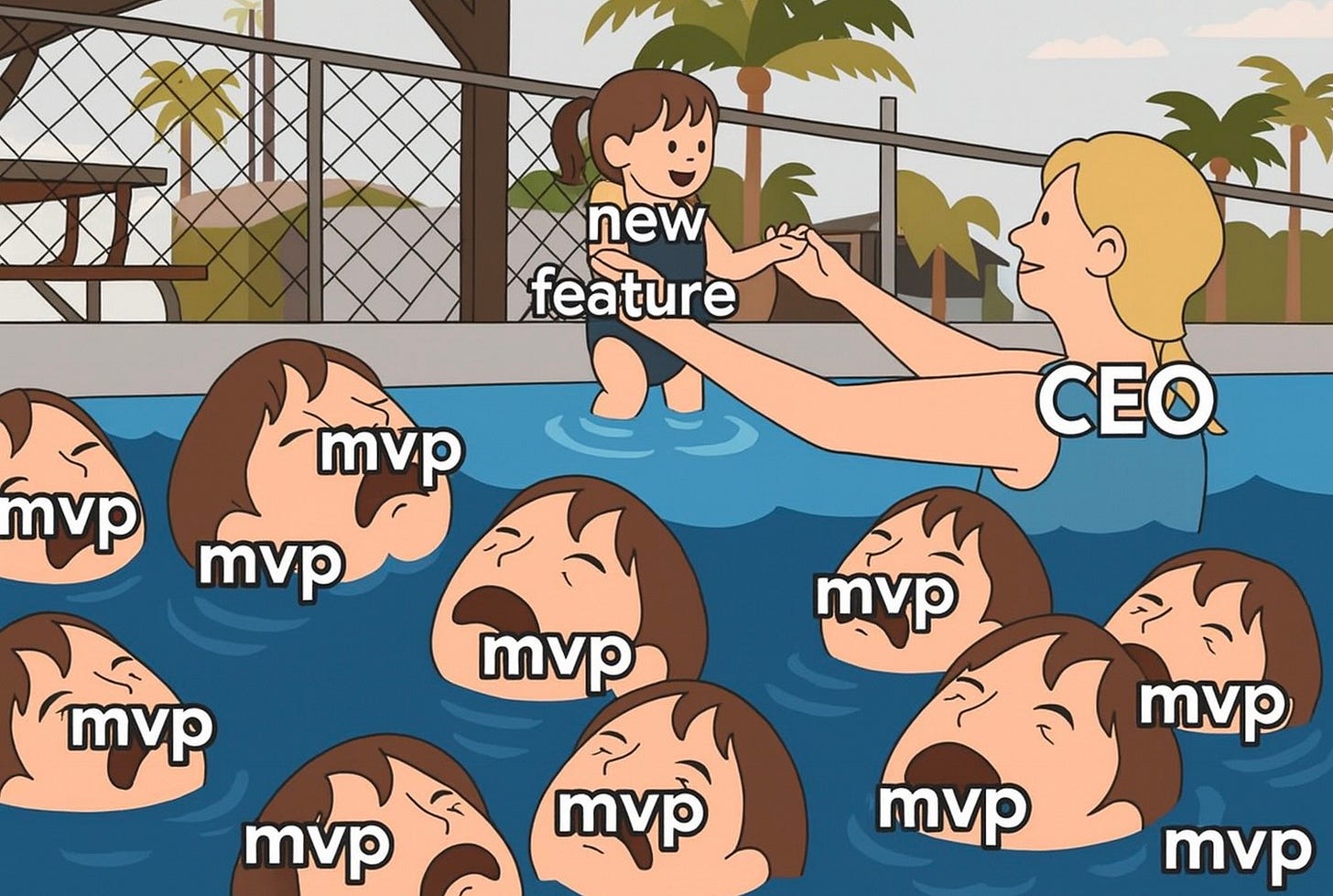

Executives like them because they’re easy to communicate: “Look how much we shipped.”

Sales loves them because they fill competitor comparison charts.

Founders fall for them because the next feature always feels like the one that unlocks growth.

But here’s the truth: features are not value.

A feature is just a capability.

Value is when a customer’s pain actually goes away.

Fail to make that distinction, and you end up in the feature factory: shipping output but not outcomes.

The hard lesson at Touchpoint

At Touchpoint, our strategy was simple: copy most of the features from the market leaders. Combine the best ideas from direct and indirect competitors.

It sounded like a path to success.

We built bells and whistles because that’s what competitors had.

But we never launched.

Why? Leadership looked at what we had and decided: “This isn’t enough compared to competitors.” So we kept adding more. More polish. More “missing features.” More scope.

The irony: in chasing completeness, we ended up with nothing. The product died under the weight of its own ambition.

That failure burned a lesson into me:

Copying features is not strategy. It’s insecurity disguised as progress.

Phishbite: starting with a clear metric

Phishbite’s mission is to reduce cybersecurity risk by reshaping user behavior.

We asked ourselves: how do we measure whether we’re delivering real value?

The answer was clear: reduction in click-through rates on simulated phishing emails.

This time, we focused our MVP on solving that core problem first.

It worked. Many companies showed steady drops in phishing click rates. But not all. Some users didn’t improve. Some companies didn’t see the effect we expected.

Now the question was harder: should we keep pushing on the same metric, or move on?

We decided to move on, partly because we were close to the bar we had set, and partly because prospects told us they wanted more general cyber hygiene training in addition to phishing simulations.

A second MVP and a mistake

We launched a micro-trainings module as a second MVP.

But this time we made a mistake: we didn’t define success metrics upfront. We assumed our competitive edge was practical content and interactivity. We got positive feedback, which felt encouraging.

But we didn’t define success criteria. Initially this wasn’t a problem. We launched an MVP for micro-trainings and got good feedback from some of our initial users and prospects.

Well done! Should we move on? We believed so.

There were a lot of things potential customers were asking for, either because competitors had them or because they believed those features would help them.

Now it became even more complicated. We had two MVPs launched. For both areas, we had feature requests as well as our own ideas for improvements.

We were dealing with these items, trying to understand the problems behind the requests and to prioritize our activities between keeping existing customers happy and acquiring new ones.

But then we started getting signals from some customers that completion rates for the micro-trainings module were quite low.

For some customers it was excellent, but not for all.

That’s when I realized it was a mistake not to have key metrics in place for the general cyber hygiene training.

Ideally, I would like to measure the real impact of these trainings, for example, whether users are now using stronger unique passwords or enabling 2FA, but that’s not easy to track.

So we decided to take a smaller step and define our initial KPI for the cyber hygiene training module: completion rate.

If users don’t complete the training, there’s no way we can expect their behavior to change.

The value of our product is not “sending phishing simulations” or “providing training modules.”

The value is changing behavior.

And solving that means doubling down on the core problem, not rushing to the next shiny feature.

The blend: qual and quant

Year one at Phishbite: qualitative insight dominated. Every customer voice felt critical.

Now, with thousands of users, quantitative data guides us more. But numbers alone don’t explain why things happen.

The real power is in combining both:

Quant shows the pattern.

Qual explains the reason.

Without both, you either drown in noise or miss the nuance.

When is it time to move on?

One of the hardest product questions is this:

When is it time to stop improving the same solution and move on to the next problem?

You can always polish. There’s no natural end.

My rule of thumb:

Set an expected bar for your core metric.

Compare to competitors when you can.

Use customer feedback in the context of value, not features.

But I don’t pretend to have the final answer. Sometimes 80% is enough. Sometimes, for your core value, you need to push to 95%.

I’d love to hear how others decide: when is “good enough” really enough?

What if I’m wrong? The Featurebase counterpoint

Sometimes I ask myself: what if I’m wrong about all of this?

There’s an Estonian startup called Featurebase that’s doing incredibly well. They built a platform where companies collect feedback on feature ideas, prioritize based on that feedback, and ship what customers ask for.

It works. They have traction. They even use their own platform to build their product.

In some sense, they’re doing exactly what I warn against: building what customers request. And yet, it justifies itself.

The way I see it, Featurebase isn’t a feature factory enabler. It’s a feedback and communication tool. It helps companies listen, close the loop, and make customers feel heard.

So maybe the deeper lesson is not “never build what customers ask for.”

It’s: don’t confuse requests with value.

Feedback is signal. But solving the problem behind the request is what creates outcomes.

Final thought

If you are a product leader or founder, remember:

Features are tools. Value is the outcome.

Your job is not to build the most features.

Your job is to solve the most meaningful problems.

Metrics will give you signals.

But the deepest insights still come from talking to customers.

I loved the read! Thank you! I never knew you went through so many versions before now.

This got me thinking - I think feature factory and building features that customers want/need come from a different place psychologically. Feature factory almost feels like a collective imposter syndrome with the teams (or management) trying to prove that they are good enough by the amount of features they have. While what feature base is doing to me resembles more experimentation. Because you have to start from somewhere and the customer is the best place to start from trying to figure out what to build. It’s just about the “why” you end up building what you’re building - is it that you build because you have to (or you’re obviously not good enough) or you build because you have a hypothesis and you want to know if yoi were right.

My own personal goal is getting much better at curiosity and experimentation, but I do agree the feature factory trap is often closer than I care to admit.

Thank you for sharing, I think it's hard question to answer Are building what users want or what users need? So the possible answers lies in qualitative feedback + analytics so our hypothesis would have a better foundation.